The U.S. Olympic Relay Program Is Finally in Good Hands

Mechelle Lewis Freeman had an hour to kill before finding out if she killed her career. She was in Eugene, Ore., for the 2022 World Athletics Championships. Freeman, in her first year as the U.S.’s women’s relay head coach, woke up on the morning of the 4 × 100 final and made a decision that, for more than a century, would have been heretical: She benched her fastest sprinter.

Aleia Hobbs had done nothing wrong. Her exchanges in the preliminary heat were clean—and the U.S had already run a 41.56, the lowest time in the world that year. But Freeman and men’s head coach Mike Marsh were in the process of totally revamping the U.S. relay program, and clean was no longer good enough. They were looking for every edge to create the most efficient possible exchanges. They had drilled their runners on technique and teamwork before the meet at relay camp, which Hobbs missed because she had COVID-19.

Freeman believes relays are a combination of art and science. She had science on her side. Data showed that the fastest baton exchanges were between Abby Steiner, who did not run in the semi, and Jenna Prandini. Now she was counting on the artists on the track.

After Steiner, Prandini, Melissa Jefferson and Twanisha Terry left the warmup area at Hayward Field for the pre-race call room, Freeman stuck around. She did not want to get drawn into idle conversation. She opted to watch the event on TV.

“It’s like you [send] your kids off to camp,” she says. “Have fun, and I’ll see you at the end. You just have an hour to think. There was nothing for me to do but just pray.”

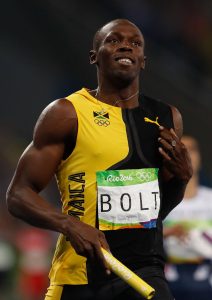

The trouble with prayer is that sometimes deities are in the other lane. Jamaica had won Olympic relay gold the year before and had just swept the individual medals in the women’s 100 in Eugene.

Freeman says she was “very anxious. At the same time, I was excited because I really believed it was going to work.”

Passing the baton seems like the easiest of Olympic tasks—the athletic equivalent of putting paint on a palette. Nobody has ever made an Olympic team simply for a masterful exchange. Even the die-hardiest of track fans do not argue about the greatest baton passers of all time. That is why Team USA’s handoff follies have been so maddening: The U.S. always excels at the hard part (producing four of the fastest people in the world) but often fails at the easy bit.

There is nothing in Olympic history quite like what the U.S. has done in men’s track relays: an extended period of dominance, followed immediately by a long stretch of ineptitude. From 1920 to 2004, American men competed in the 4 × 100 in 19 Olympics. They won 15 gold medals and two silvers. Since then, the U.S. men have made regular summer trips to DQ: They have been disqualified in three of the last four Olympics, as well as the ’09, ’11 and ’15 world championships. (The Americans also forfeited their lone Olympic medal, a silver in ’12, due to a positive drug test.)

After the U.S. screwed up another handoff and finished sixth in qualifying in Tokyo, American legend Carl Lewis called it “a total embarrassment and completely unacceptable for a USA team to look worse than the AAU kids I saw.” The U.S. women have a much better recent track record, but they have had their own handoff nightmares: They were DQ’d from the Olympics in 2004 and again in ’08, when Freeman ran the second leg and then watched as her teammates botched the final exchange.

The disqualifications don’t even capture all the legal but slow exchanges that have cost the U.S.